Blog

Sometimes I joke that we’ve been talking about the Millennial generation for so long, they got old.

Old enough, at least, to start families. And thus Millennials were a central focus at the Juvenile Product Manufacturers Association conference in California, where I spoke earlier this month.

The JPMA represents companies that serve the prenatal to toddler phase of parenting--car seats, strollers, feeding, furniture and, increasingly, baby monitors. And not just baby monitors, but really smart baby monitors.

The JPMA represents companies that serve the prenatal to toddler phase of parenting--car seats, strollers, feeding, furniture and, increasingly, baby monitors. And not just baby monitors, but really smart baby monitors.

The “Connected Nursery” was a big topic at the show. Sleep trackers like the Mimo, integrated into little kimonos or body suits, now connect wirelessly with, for example, your Nest thermostat, so if baby is too warm, the nursery heat turns down. Or your video monitor will notify you when baby starts to move. Smart scales track and record baby weight precisely. And smart diaper clips will let you know when baby needs changing.

There is even a smart sound machine that detects when baby is stirring and will play soothing natural sound, or lullabies, or project animations on the ceiling...and if all else fails, puts Mom on the line to have a two-way chat. All, of course, controlled by a smartphone app.

Clearly it’s early days for these devices and physicians warn they’re no substitute for vigilant parents. There is even suggestion that some of these devices should be approved by the FDA. But as a trend, it’s inevitable.

And there’s more in store. Besides watching and enjoying baby, of course, the other new parent activity is worrying and asking for advice. Already there are simple applications for Amazon’s voice-powered Alexa that will verbally answer a limited range of parenting advice questions.

It’s not hard to imagine a future in which an artificial intelligence--like IBM’s Watson or Google’s DeepMind--can be loaded with an encyclopedic body of baby and childcare information. Mom or Dad will be able to ask aloud, any time, day or night, their crucial questions: “Is this rash normal?” And get an immediate, authoritative answer.

Or, that intelligent baby advisor in the cloud could monitor the smart scales and other monitors in the “Connected Nursery” so it can answer questions like “Is my baby’s weight normal today?”

The only question it probably can’t answer is whether your baby is the cutest baby ever. For that, you still need grandparents.

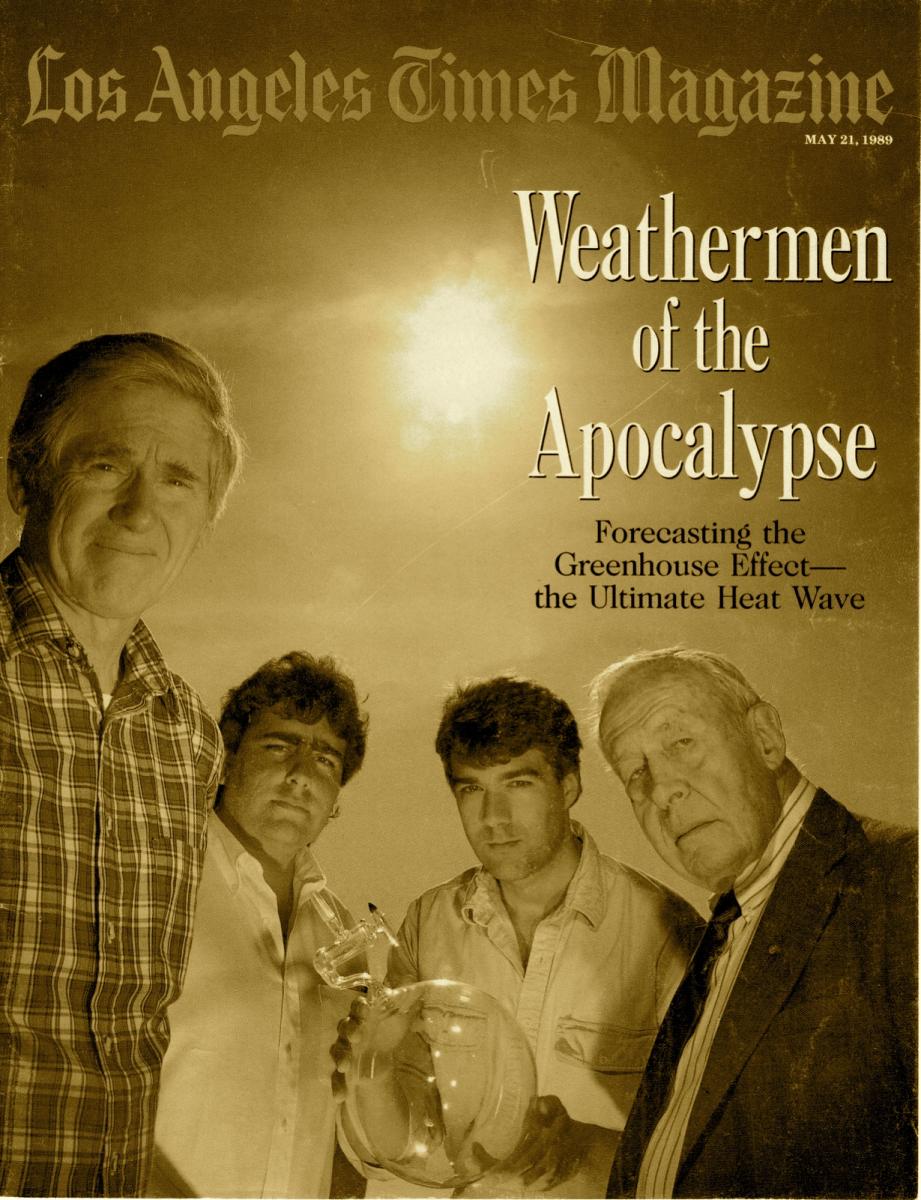

As a science writer I always looked for stories about the future, so it’s no surprise that I started covering global warming and climate change during the late 80’s. Recently going through my files I ran across one of those stories, from 1989, that ran on the cover of The Los Angeles Times Sunday magazine.

What’s interesting now is how clear the science was, even back then--and how relatively uncontroversial the topic seemed. I wrote about the researchers at Scripps Oceanic Laboratory, who were then arguably the leaders in atmospheric research.

What’s interesting now is how clear the science was, even back then--and how relatively uncontroversial the topic seemed. I wrote about the researchers at Scripps Oceanic Laboratory, who were then arguably the leaders in atmospheric research.

The Scripps researchers seemed confident that there was still time to slow or even stop the warming trend, as long as society acted relatively quickly. I think back then, the success in the Seventies of the global community at banning Freon--to prevent atmospheric ozone destruction--was still a recent memory. Of course the world would rally to prevent an even bigger hazard.

And back then, there were no climate change skeptics for me to quote--something I would have done in my normal science-writing practice. Certainly there was no one from the fossil fuel industry to quote: back then, their own researchers were also concerned about global warming.

What strikes me now about the story is its calm innocence, given how politically charged and divisive the issue has become in the United States. Back then, I don’t think anyone on the science side suspected what kind of opposition waited ahead as the fossil fuel industry moved to protect its commercial interests.

Ironically, they learned quickly. Within a couple of years two of the Scripps researchers I profiled in the article were deep into the political thickets. Roger Revelle, sometimes called “the father of global warming”, under dubious circumstances was made co-author of an article that questioned the need for action on the issue. His young assistant, Justin Lancaster, publicly protested that his professor hadn’t been fully aware of the content of the article and that it didn’t reflect his views.

Very quickly, an early group of global warming deniers sued Lancaster. To avoid a lawsuit he couldn’t afford, the young researcher withdrew his statement--although years later, as Revelle’s apparent skepticism was repeatedly cited, he went back on the record.

But perhaps we should have suspected back then just how powerfully the fossil fuel industry would attack the science. It was, after all, much earlier in the century that another writer, Upton Sinclair, observed that "It's hard to get a man to understand a thing when his paycheck depends on his not understanding it."

For anyone interested in a bit of scientific nostalgia, a PDF of the article is here.

I recently helped with a research paper on the future of “algorithms”--a once-techy term that now generically refers to computer software that uses rules to make decisions. Software, for example, that takes complex data like your financial information and then generates a credit score. Algorithms now do everything from pricing airline tickets in real time to perfecting long-term weather forecasts.

The basic question of the research was simple: is the increasing use of algorithms to manage society good or bad? As with almost any technology, the answer, of course, is both--but for the most part algorithms are invisible.

The basic question of the research was simple: is the increasing use of algorithms to manage society good or bad? As with almost any technology, the answer, of course, is both--but for the most part algorithms are invisible.

There’s one technique, however, that I think will attract increasing attention: the combination of smart algorithms with computer vision.

Video surveillance cameras, for example, in airport parking lots, can now be connected to smart algorithms to analyze movement. They can tell the difference between a traveler returning to their car and someone who is casing vehicles for smash-and-grab thefts. In the latter case, the software will alert a human security guard who comes out to check the situation. The system never dozes off or gets bored or distracted. It’s always watching.

So too are the cameras in a recent retail store application, where the security cameras observe not only the customers, but the employees as well. Using facial recognition, the cameras track every interaction each sales clerk has with the public.

At the end of the day, algorithms produce a report on just how the clerk performed--did they ignore customers? Were they shy about approaching people? How did their behavior relate to the sales they rang up on the register?

As the creators of the system put it, the report give managers the opportunity of a “teachable moment” with each employee at the end of the day.

Or maybe it’s more of a threatening moment.

A few weeks ago in New York I was interviewed for a History Channel documentary called This is History: 2016. The show is based on a new Pew Research Center poll that asked four different American generations--from Millennials through the Greatest Generation--to name the 10 most significant historical events of their lifetimes.

For starters, the differences between generations clearly reflected their ages: for Boomers and the Greatest Generation, civil rights, the JFK assassination and Vietnam figured large. Gen X and the Millennials, on the other hand, named school shootings like Columbine and Sandy Hook, or terrorist attacks such as Orlando and the Boston Marathon.

Interestingly, each generation also had its own unique historical recollection not shared with any other generation: the Korean War for the Greatest Generation, Martin Luther King’s assassination for Boomers, the Challenger disaster for Gen X, and the Great Recession for Millennials.

In the end, however, all generations agreed on five key events: JFK’s assassination, September 11, Obama’s election, the Iraq/Afghanistan wars--and the tech revolution.

That last choice is noteworthy, considering that “the tech revolution” is neither a heart-stopping historical moment, nor an intensely emotional national experience. No one ever asks “Where were you when you heard about the tech revolution?” Yet technologic change has a place in the national memory that ranks with major social movements and tragic assassinations.

That’s what I talked about in the History Channel interview. It’s obvious that 2016 will be remembered historically for the rise of nationalistic populism, as evidenced by the Brexit referendum and Donald Trump’s victory. And there are, of course, lots of explanations for surging populism, ranging from anxiety over immigration to globalism and middle class malaise.

Yet I think that underlying this political upheaval is another chapter in the tech revolution: the oncoming ability of machines and software to replace human labor--from fast food workers and truck drivers to young lawyers and accountants. This chapter is still on its first pages, but already a broad segment of the population feels the economic earth moving beneath their feet: a vague sense that the fundamentals of labor and employment are changing, and not in a good way for human beings.

Of course that’s far too nebulous a threat to win a political campaign, so politicians turn to easier targets like illegal immigrants and overseas factories. But I think history will ultimately remember the populist uprising of 2016 as a distant early warning signal of a much larger economic crisis to come. And that crisis will, for yet another generation, be among their ten most significant events.

Someone asked me recently what were the biggest challenges ahead in the HR world. I spend a lot of time talking with those key figures in business--the people who manage the people--and at the moment I'd say there are three broad areas:

--The soft-skills gap in some younger workers. Broadly, these are skills involving communications, collaboration, unstructured problem-solving, etc. I worked with one Fortune 500 firm last year that’s planning a "remedial social skills” course for certain new hires.

This isn’t the same tired old knock on the Millennials—it’s rather recognizing that technology inadvertently impacts the development of soft skills for at least some in adolescence and emerging adulthood. It’s a fixable issue that needs to be addressed in K-12 and college, but until that happens, the remediation will fall to employers.

--The challenge of virtual workplaces. Whether managers like it or not, we are moving to a much more dispersed, partially virtual workforce. The drivers include the cost of real estate and energy, the burden of commuting (including traffic congestion), and sometimes the preferences of the talented young workers we want.

--The challenge of virtual workplaces. Whether managers like it or not, we are moving to a much more dispersed, partially virtual workforce. The drivers include the cost of real estate and energy, the burden of commuting (including traffic congestion), and sometimes the preferences of the talented young workers we want.

I worked with a white-shoe law firm in Manhattan recently who basically promised a partnership to a young woman who graduated Harvard Law with a stellar record. She turned them down—she’d interned for them one summer, disliked the lifestyle—and said she would take a job, but she wanted to live in Colorado. The older partners were stunned, but finally gave in. She works in Colorado, where she skis and hikes, and commutes into Manhattan once a month.

Of course the physical office is not going away—but it will be more of a place for collaboration than solitary work. And it will be festooned with telepresence video screens that connect separate offices via always-on “windows”. Among the challenges for HR: how do you create corporate culture and evaluate employees in a mixed real-virtual workplace? What are the metrics to determine whether a job or business trip is better handled in the real world or virtually?

—The looming issue of white collar automation. Cognitive computing—the newest evolution of artificial intelligence--is performing many low-level white collar and even professional tasks more cheaply, and often better, than humans. We already see the impact in services, like accounting and law and advertising, where the entry-level jobs, the traditional stepping stones to full professional responsibility and client contact, are being automated. What do you do with new workers while they are learning the practicalities of the job?

But white collar automation will also ultimately strike more broadly, and result in repeated downsizing and restructuring in many sectors. A key response for HR is to encourage employees toward skills that can’t or won’t be done by computers--and also how to work with cognitive computers in collaborative ways.

—The new jobs marketplace. The aging-out workforce, the shortfalls of our educational system, and the move toward highly specialized job functions, means that by next decade employers may be chasing a smaller and smaller pool of qualified candidates. And those job candidates may not fully believe in the ability of any corporation to offer them long-term secure careers.

Taken to its extreme, one could imagine young workers with highly valued of-the-moment skills marketing themselves in an online marketplace in which employers compete and bid up salaries, a bit like professional athletes. These in-demand employees want to maximize their current payout, knowing that as they grow older they may need to take time off to retrain and re-enter the workforce.

Last week Farhad Manjoo, the technology columnist for The New York Times, had a thoughtful piece on the death of the early futurist Alvin Toffler, most famous for his book Future Shock.

Last week Farhad Manjoo, the technology columnist for The New York Times, had a thoughtful piece on the death of the early futurist Alvin Toffler, most famous for his book Future Shock.

Toffler’s thesis back in 1970 was simple: “Change is avalanching upon our heads,” he wrote, “and most people are grotesquely unprepared to cope with it.”

Forty-six years later, says Manjoo, ”...it seems clear that his diagnosis has largely panned out, with local and global crises arising daily from our collective inability to deal with ever-faster change.” Yet at the same time fewer and few institutions are even thinking about the future in substantive ways.

It wasn’t always thus: in the Seventies, various organizations, such as RAND and SRI worked for the government projecting the future of global politics and nuclear weapons. The Office of Technology Assessment was established by Congress in 1975 to look at the future impact of impending legislation.

But by the mid-90’s, when the OTA was shut down, the idea of futurism was distinctly tarnished. Says Manjoo: “Futurism’s reputation for hucksterism became self-fulfilling as people who called themselves futurists made and sold predictions about products, and went on the conference circuit to push them.”

Alas, too true. When I began speaking about the future I was most reluctant to use the futurist word. Having spent twenty years in hands-on work inventing new media, I didn’t take futurists seriously: they often lacked technical understanding, or real business experience (or both). Too often their predictions veered off into either science fiction or simply what they’d like to see happen. Futurists became famous for their perennial predictions of flying cars. (The one below was supposed to arrive in 1967.)

Thus, when The New York Times asked me to be Futurist-in-Residence, I tried to talk them out of that title. I’d been around journalists for a long time and I feared that no one in the NYT newsroom was likely to take someone called a “futurist” very seriously. But the newspaper insisted, and in the end I decided that when The New York Times wants to call you something, you might as well go with it.

As it turned out, the title worked. When there is a “futurist” in the room, it gives everyone permission to untether, at least briefly, from quarterly reports and annual budgets. The time spent thinking out five to eight years is then very helpful when discussion returns to the here-and-now. A number of the organizations I’ve worked with in the past few years have initiated real changes in directions and strategy after a few hours of contemplating the world of the early Twenties.

Futurism is not dead; rather, as foresight has left the political process it has instead become more local. And it's still a very good discipline for organizations and corporations to pursue.

As another early futurist, Kenneth Boulding, once said: “The future will always surprise us, but we must not let it dumbfound us.” That's the very least we should ask from our futurists.

Here's a recent interview I did with Speaking.com, one of the leading speaking agency Websites:

And another interesting project with The Atlantic:

One morning a few weeks ago three New York City policemen came to my door. Not ordinary officers, but members of the Counter Terrorism Task Force, working with the FBI. They wanted me to know that my name and address had just appeared on a ISIS hit list of 3,600 New Yorkers, released on a messaging app under the tag We Want Them #Dead.

One morning a few weeks ago three New York City policemen came to my door. Not ordinary officers, but members of the Counter Terrorism Task Force, working with the FBI. They wanted me to know that my name and address had just appeared on a ISIS hit list of 3,600 New Yorkers, released on a messaging app under the tag We Want Them #Dead.

Great way to start the day. However, the officers were quick to say that the FBI didn’t think this was a serious threat--there wasn’t a clear pattern to the names on the list, and some of the information was quite out-of-date. Of course, one said, handing me his card, if you see anything unusual, give us a call. But it appeared to be almost random New York names and addresses picked up from somewhere on the Internet.

Random? I asked to see some pages from the list. By far the most names were from my borough, Brooklyn. Then I recognized a few neighbors and immediately suspected what had happened.

Brooklyn may be the world center of worthy causes. Universal pre-K, ban plastic bags, widen the bicycle lanes--you name it, and we have a group for it. I’m partial to a worthy cause once in a while, and so are some of my more activist neighbors. We sign petitions, donate, end up on mailing lists....and in databases.

Many of the worthy causes sooner or later win (or lose) their battles, run out of money, or just fade away. But sometimes their Internet databases live on, perhaps tended by a volunteer with limited time, perhaps not tended at all.

Aging database software is easy prey for even low-skilled hackers. I suspect that somewhere among the defunct worthy causes is where ISIS collected their list. Why did they even bother? As a kind of psychological warfare, perhaps, as well as a way to get publicity and waste some U.S. law enforcement time.

But there’s a larger issue here. For my audiences, Internet security is at the top of everyone’s mind. Many fear, from the stories they’ve read, that real online security is impossible. I remind them that most of the big, notorious computer hacks we read about actually used very simple techniques--more often than not, exploiting human fallibility rather than esoteric technology. Those human foibles range from clicking on links in unknown emails to, well, leaving a database abandoned online.

The solution is broader than just trying to educate employees; by then it's probably already too late. We need education that starts in elementary school. We teach kids how to cross the street safely, and that if they leave their bike far from home, sooner or later it’s going to disappear. It becomes what we call "common sense." Online security awareness should also be taught from an early age--so that leaving a database of names and addresses untended on the Internet is as unthinkable as leaving for vacation with your front door open.

This month the big news in computer science circles was that Google’s AlphaGo software beat the world’s top player in the ancient game of Go, winning four out of five games in a million-dollar contest.

This month the big news in computer science circles was that Google’s AlphaGo software beat the world’s top player in the ancient game of Go, winning four out of five games in a million-dollar contest.

The win is significant because Go is a far more complex game than chess. Computers can win at chess simply by computing all the implications of every possible move on the board--that’s millions of possibilities, but entirely doable by a fast computer. Go, on the other hand, has so many possible moves that human Go champions develop a kind of intuition that has been impossible to imitate in software.

Until now. The AlphaGo program has intuition--a broad sense of the game that it learned, first by studying the records of previous matches and then by playing millions of practice Go games against itself. And the computer’s intuition appears to be better, or at least different, than the human version. As one high-level Go player commented: “It’s like another intelligent species opening up a new way of looking at the world...and much to our surprise, it’s a new way that’s more powerful than ours.”

This so-called cognitive computing--the ability to learn from data and experience and develop new skills--is a key piece of artificial intelligence. And it has the potential to impact a broad range of white-collar jobs.

This will start with entry-level jobs. Take law as an example. As the saying goes, law school doesn’t teach you to practice law. So, traditionally, law firms keep new lawyers busy doing work like research, sorting through evidence in cases, and drafting contracts. Along the way, they learn the practical aspects of law.

This will start with entry-level jobs. Take law as an example. As the saying goes, law school doesn’t teach you to practice law. So, traditionally, law firms keep new lawyers busy doing work like research, sorting through evidence in cases, and drafting contracts. Along the way, they learn the practical aspects of law.

Now, however, intelligent software can do many of those entry-level legal jobs, often better and always more cheaply. Big accounting firms are going through a similar transition, as more and more accounting tasks are automated. And many entry-level corporate jobs also turn out to be easily automated.

These perturbations in the white-collar world are early warning signs of a much broader social issue. Sooner or later, artificial intelligence and robots will eliminate a broad swath of well-paying jobs and it’s not at clear where new jobs--with equivalent salaries--will come from. The challenge from smart computers will be very real, and this time, it won’t be a game.

It was only twelve years ago that the Department of Defense sponsored the first 150 mile autonomous vehicle race in the California desert, with a prize of $1 million. Fifteen vehicles, including entries from CalTech and Carnegie Mellon, started the race.

None finished. The best performer went only 11 miles before breaking down.

None finished. The best performer went only 11 miles before breaking down.

The progress since then has been amazing. Everyone from Audi to Volvo has announced self-driving cars, and Google is already running a fleet of autonomous vehicles around their California campus.

Some of the key technologies are now commercially available: parallel parking assistance, adaptive cruise control, lane-keeping support, and--for the Silicon Valley elite--Tesla’s autopilot. And last month, the Federal government promised to spend $4 billion in autonomous vehicle research over the next decade.

No wonder that, in nearly every speech I give these days, someone wants to know when they’ll get their driverless car.

That’s hard to answer. The promise is great--most obviously, self-driving cars in which the driver becomes a passenger, free to watch videos or catch up on work without paying any attention to the road. Even better: a world in which you don’t even need to own a car. There will be large fleets of self-driving cars and you simply summon one to your front door whenever you want a ride.

It is, however, not a straight line to that future. For starters, of course, traffic laws need to be changed and insurance responsibilities must be addressed.

There are also, inevitably, human factors. Cautious autonomous vehicles may find it technically difficult to share the roads with unpredictable, risk-taking humans. Consider a busy intersection with four-way stop signs. A law-abiding driverless car could be stuck for hours as impatient human drivers aggressively cut in front of it.

The early days of the automobile itself were marked by enough collisions with horses that some cities declared “automobile only” streets. It’s not unlikely that by the mid-Twenties, we’ll also see “smart vehicle lanes” in which autonomous cars communicate with each other, allowing both higher speeds and greater safety. The photo at left shows a Swedish experiment in which four different vehicles are locked together electronically, moving at high speed yet only a few feet apart.

The early days of the automobile itself were marked by enough collisions with horses that some cities declared “automobile only” streets. It’s not unlikely that by the mid-Twenties, we’ll also see “smart vehicle lanes” in which autonomous cars communicate with each other, allowing both higher speeds and greater safety. The photo at left shows a Swedish experiment in which four different vehicles are locked together electronically, moving at high speed yet only a few feet apart.

Finally, one of the biggest dilemmas is already on the horizon. California legislators want to make self-driving cars legal--as long as there is always a licensed and insured human at the wheel, able to take control in emergencies.

Sounds like a sensible first step. But how do you make sure the human is actually paying attention?

We already have trouble forcing drivers to pay attention to the road when there are digital distractions in the car. A “driver” in some future automated car is likely to be deep into watching, say, Season 18 of The Walking Dead when the emergency happens--not exactly ready to spring into action.

Self-driving cars? Most certainly. But weaving these wonders into the existing fabric of society may be almost as difficult as the technology itself.