Blog

I've spoken to dozens of audiences lately about AI, and I've never seen a technology elicit such a range of emotions--from wonder to cautious optimism to deep concern about future job loss and even super-intelligent robot overlords.

When audiences ask what most worries me in the immediate future, the answer is simple. It is deepfakes and their potential impact on society--and specifically, the political process.

In 2024, about 40 countries, accounting for over 1.5 billion people, will hold national elections. This is likely the biggest year in history for the democratic process. And disinformation and deepfakes will play a role--both home-grown and deployed as weapons by hostile nations who hope to see democracies collapse.

i've followed all the efforts around the globe to come up with "labelling" or "watermarking" systems for AI-generated content. And it's a mess. Lots of proposals in many countries, and no clear common path forward in terms of definitions, standards or enforcement.

But--we may be trying to fix the wrong part of the problem, and I wrote about it in last Sunday's Los Angeles Times. It turned out the best way to describe my thinking is to take a look backward, from five years in the future....

Cast your mind forward. It’s Nov. 8, 2028, the day after another presidential election. This one went smoothly — no claims of rampant rigging, no significant taint of skulduggery — due in large part to the defeat of deepfakes, democracy’s newest enemy.

Is such a future possible? So far, neither government nor the tech industry has agreed on effective guardrails against deepfakes. But this FAQ (from five years in the future) shows that the events of 2024 may well force the issue — and that a solution is possible.

This year I’ve spoken about little else but AI, and appropriately so: while artificial intelligence has been an emerging technology for some decades, the rise of so-called generative AI, typified by ChatGPT, has been a turning point in public attention.

Audiences have countless questions: How will AI impact employment? What will it mean for content owners and copyright? What are the social implications of flawless deep fakes? What regulations are needed to prevent abuses? Will those regulations stifle innovation? Recently I wrote about how AI could change education.

Audiences have countless questions: How will AI impact employment? What will it mean for content owners and copyright? What are the social implications of flawless deep fakes? What regulations are needed to prevent abuses? Will those regulations stifle innovation? Recently I wrote about how AI could change education.

And much more. Yet thus far I’ve been asked little about what is most certainly the most radical AI prediction: that it will evolve to threaten humanity. Leading AI scientists have warned that this invention may lead to our own extinction.

There’s an interesting historical parallel to those fears, one I recently wrote about for the Los Angeles Times:

JUNE 25, 2023 3 AM PT - In the summer of 1974, a group of international researchers published an urgent open letter asking their colleagues to suspend work on a potentially dangerous new technology.

The letter was a first in the history of science — and now, half a century later, it has happened again.The first letter, “Potential Hazards of Recombinant DNA Molecules,” called for a moratorium on certain experiments that transferred genes between different species, a technology fundamental to genetic engineering.

The letter this March, “Pause Giant AI Experiments,” came from leading artificial intelligence researchers and notables such as Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak. Just as in the recombinant DNA letter, the researchers called for a moratorium on certain AI projects, warning of a possible “AI extinction event.”

Some AI scientists had already called for cautious AI research back in 2017, but their concern drew little public attention until the arrival of generative AI, first released publicly as ChatGPT. Suddenly, an AI tool could write stories, paint pictures, conduct conversations, even write songs — all previously unique human abilities. The March letter suggested that AI might someday turn hostile and even possibly become our evolutionary replacement.

Although 50 years apart, the debates that followed the DNA and AI letters have a key similarity: In both, a relatively specific concern raised by the researchers quickly became a public proxy for a whole range of political, social and even spiritual worries.

The recombinant DNA letter focused on the risk of accidentally creating novel fatal diseases. Opponents of genetic engineering broadened that concern into various disaster scenarios: a genocidal virus programmed to kill only one racial group, genetically engineered salmon so vigorous they could escape fish farms and destroy coastal ecosystems, fetal intelligence augmentation affordable only by the wealthy. There were even street protests against recombinant DNA experimentation in key research cities, including San Francisco and Cambridge, Mass. The mayor of Cambridge warned of bioengineered “monsters” and asked: “Is this the answer to Dr. Frankenstein’s dream?”

The recombinant DNA letter focused on the risk of accidentally creating novel fatal diseases. Opponents of genetic engineering broadened that concern into various disaster scenarios: a genocidal virus programmed to kill only one racial group, genetically engineered salmon so vigorous they could escape fish farms and destroy coastal ecosystems, fetal intelligence augmentation affordable only by the wealthy. There were even street protests against recombinant DNA experimentation in key research cities, including San Francisco and Cambridge, Mass. The mayor of Cambridge warned of bioengineered “monsters” and asked: “Is this the answer to Dr. Frankenstein’s dream?”

In the months since the “Pause Giant AI Experiments” letter, disaster scenarios have also proliferated: AI enables the ultimate totalitarian surveillance state, a crazed military AI application launches a nuclear war, super-intelligent AIs collaborate to undermine the planet’s infrastructure. And there are less apocalyptic forebodings as well: unstoppable AI-powered hackers, massive global AI misinformation campaigns, rampant unemployment as artificial intelligence takes our jobs.

The recombinant DNA letter led to a four-day meeting at the Asilomar Conference Grounds on the Monterey Peninsula, where 140 researchers gathered to draft safety guidelines for the new work. I covered that conference as a journalist, and the proceedings radiated history-in-the-making: a who’s who of top molecular geneticists, including Nobel laureates as well as younger researchers who added 1960s idealism to the mix. The discussion in session after session was contentious; careers, work in progress, the freedom of scientific inquiry were all potentially at stake. But there was also the implicit fear that if researchers didn’t draft their own regulations, Congress would do it for them, in a far more heavy-handed fashion.

With only hours to spare on the last day, the conference voted to approve guidelines that would then be codified and enforced by the National Institutes of Health; versions of those rules still exist today and must be followed by any research organization that receives federal funding. The guidelines also indirectly influence the commercial biotech industry, which depends in large part on federally funded science for new ideas. The rules aren’t perfect, but they have worked well enough. In the 50 years since, we’ve had no genetic engineering disasters. (Even if the COVID-19 virus escaped from a laboratory, its genome did not show evidence of genetic engineering.)

The artificial intelligence challenge is a more complicated problem. Much of the new AI research is done in the private sector, by hundreds of companies ranging from tiny startups to multinational tech mammoths — none as easily regulated as academic institutions. And there are already existing laws about cybercrime, privacy, racial bias and more that cover many of the fears around advanced AI; how many new laws are actually needed? Finally, unlike the genetic engineering guidelines, the AI rules will probably be drafted by politicians. In June the European Union Parliament passed its draft AI Act, a far-reaching proposal to regulate AI that could be ratified by the end of the year but that has already been criticized by researchers as prohibitively strict.

No proposed legislation so far addresses the most dramatic concern of the AI moratorium letter: human extinction. But the history of genetic engineering since the Asilomar Conference suggests we may have some time to consider our options before any potential AI apocalypse.

Genetic engineering has proven far more complicated than anyone expected 50 years ago. After the initial fears and optimism of the 1970s, each decade has confronted researchers with new puzzles. A genome can have huge runs of repetitive, identical genes, for reasons still not fully understood. Human diseases often involve hundreds of individual genes. Epigenetics research has revealed that external circumstances — diet, exercise, emotional stress — can significantly influence how genes function. And RNA, once thought simply a chemical messenger, turns out to have a much more powerful role in the genome.

Genetic engineering has proven far more complicated than anyone expected 50 years ago. After the initial fears and optimism of the 1970s, each decade has confronted researchers with new puzzles. A genome can have huge runs of repetitive, identical genes, for reasons still not fully understood. Human diseases often involve hundreds of individual genes. Epigenetics research has revealed that external circumstances — diet, exercise, emotional stress — can significantly influence how genes function. And RNA, once thought simply a chemical messenger, turns out to have a much more powerful role in the genome.

That unfolding complexity may prove true for AI as well. Even the most humanlike poems or paintings or conversations produced by AI are generated by a purely statistical analysis of the vast database that is the internet. Producing human extinction will require much more from AI: specifically, a self-awareness able to ignore its creators’ wishes and instead act in AI’s own interests. In short, consciousness. And, like the genome, consciousness will certainly grow far more complicated the more we study it.

Both the genome and consciousness evolved over millions of years, and to assume that we can reverse-engineer either in a few decades is a tad presumptuous. Yet if such hubris leads to excess caution, that is a good thing. Before we actually have our hands on the full controls of either evolution or consciousness, we will have plenty of time to figure out how to proceed like responsible adults.

There’s little doubt: artificial intelligence is coming after human jobs, for everyone from the customer service rep on the 800 line to the young lawyer with a shiny new degree.

The key to this onslaught is machine learning—software that can train itself for jobs, rather than depend on strict programming by humans. The technology, in development for decades, has accelerated rapidly in the last ten years.

An early example of the technology was in 2016, when a computer called AlphaGO beat the world champion at the ancient game Go. Go is an incredibly complex game with 391 pieces but fairly simple rules—meaning it has a multitude of possible moves. Chess has about 20 plausible opening moves; Go has hundreds. Go Masters teach the game through metaphors and similes, rather than firm rules.

Researchers thought it would take until 2030 to teach a computer to win at Go. Then came self-teaching AI. The researchers at Deep Mind programmed two computers with the rules of Go, and then had them play each other, millions of times, learning constantly. The researchers then pitted the self-taught software against the reigning world champion and it beat him 4 out of 5 games—entirely self-taught. Another Go master, watching the game, said “It’s like another intelligent species opening up a new way of looking at the world.”

In recent years, with names like cognitive computing or deep learning, self-teaching AI has been everywhere: sorting through piles of evidence for lawyers; reading X-rays; creating new formulas for pharmaceuticals or battery electrodes; even developing a novel alloy for a cheaper US nickel. AI has also moved into the visual world—making robot vision far smarter, and also creating new images on its own, from cloning dead movie stars to creating art that actually wins prizes in competition.

The latest shock has been the success of the machine learning program ChatGPT in imitating human writing. It’s called a “large language model”—software that has learned to write like a human by reading and analyzing the vast amounts of digital content stored on the Internet. All you do is give it a “prompt”, such as: “I would like you to write an 800 word article about the future of artificial intelligence, giving examples of how it will be used and what the impact will be for humans and work.” Moments later, ChatGPT comes back with the article.

The website CNET has already started to use AI to write its news articles. Multiple companies are developing customer service representative apps that use the new technology. (McDonalds has for several years been testing robot order-takers in its drive-thru lanes.) Some bloggers use ChatGPT to craft their posts—you simply give the program a brief overview of what you’d like to discuss, and the software turns out a complete blog post. The results aren’t perfect, but basically you’ve got a first-draft that’s close to finished. (A few bloggers have used ChatGPT to write a blog post on “What is ChatGPT?”)

And finally, high schools and colleges are already banning access to ChatGPT on campus, fearing that students will use it to write their essays. And in fact, some already do: one professor in Michigan busted a student when they handed in a paper that was “suspiciously coherent and well-structured.”

Teachers are quickly adapting to the new reality. Some require students to write first drafts of essays while sitting in class. Software is being designed that will detect ChatGPT-authored essays. Colleges are even considering dropping the essay requirement on their student applications.

Teachers are quickly adapting to the new reality. Some require students to write first drafts of essays while sitting in class. Software is being designed that will detect ChatGPT-authored essays. Colleges are even considering dropping the essay requirement on their student applications.

Those are defensive reactions. Some teachers are actively adopting Chat GPT in class as a teaching device, generating text that then drives classroom discussion. And, in fact, students need to be familiar with how to use automatic writing software—because it will ultimately be common in everyday life and business.

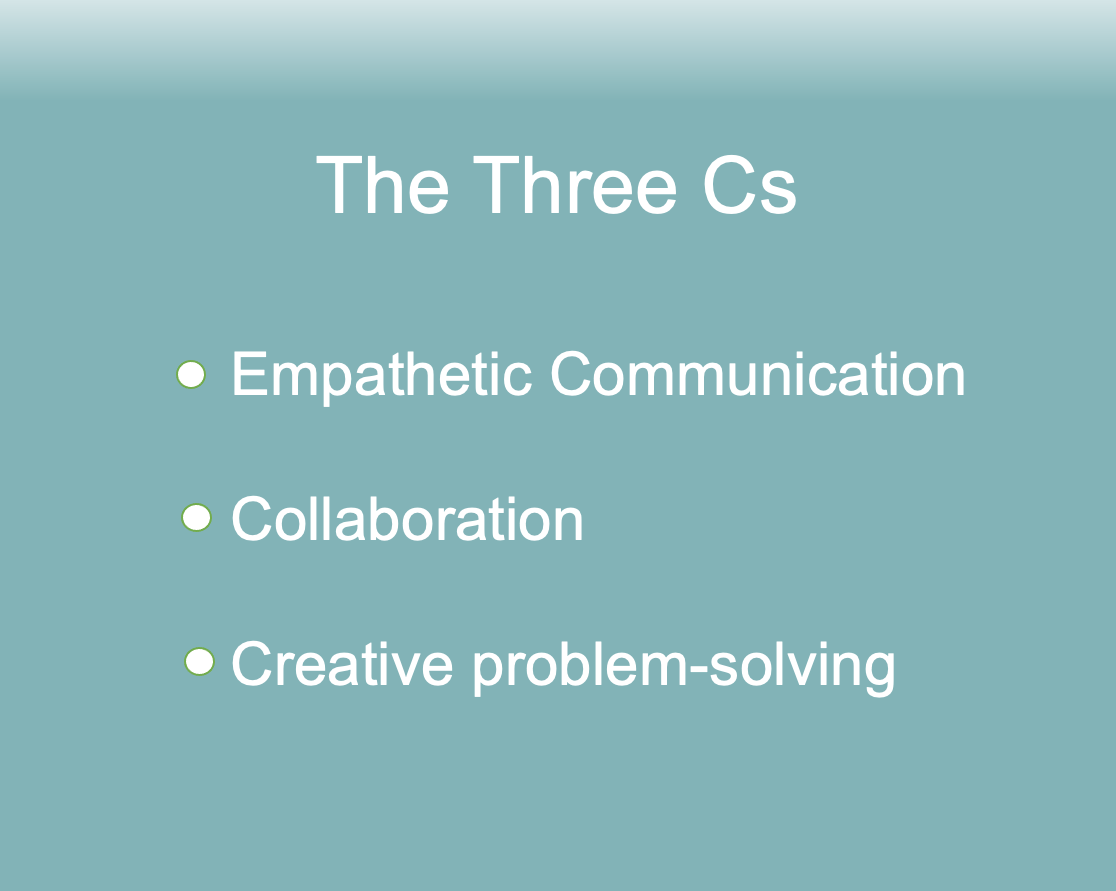

But perhaps the biggest lesson for teachers from ChatGPT is this: education must identify the unique human skills that AI and robots can’t duplicate. That will be crucial for future workers. I call these skills Three C’s.

Communication with Empathy

An AI customer service rep will be extremely good at telling you everything about life insurance tailored to your needs. An empathetic human will be the one who talks you into raising the policy from $500,00 to $1,000,000.

Collaboration

There is a special energy in having multiple minds in the same room, brainstorming about a problem or challenge. Work to make AIs collaborate has been slow, and it’s not clear it will have a similar power as the human version.

Creative problem solving

These are problems where the boundaries for a useful answer are unclear. If you’re a city looking to put in a new parking lot, AI will do a brilliant job of going through traffic density, accident reports, legal issues, zoning, and construction costs, to pinpoint the most efficient place for new parking. But an AI will probably not ask: “Do we really want a new parking lot?”

These three skills are, of course, innately human abilities—but they are skills that young students, surrounded by distracting technology, may not learn or practice on their own.

Students need to be taught, in real life, and practice with one another.

Not coincidentally, educators will soon face a challenge to their own profession: AI will ultimately do part of what teachers do today, particularly in factual areas like math or chemistry or grammar. And so for their own job futures as well, teachers should begin to focus on the skills that can only they can teach: the Three C’s.

Can government keep up with the accelerating rate of technologic change? The answer is, usually not. In the US, at least, government moves slowly and is captive to multiple conflicting influences. Legislators react after problems arise, and even then may not fully understand the underlying technology.

Instead, insurance companies may become the real regulators of new technology.

Instead, insurance companies may become the real regulators of new technology.

Consider autonomous vehicles. Some states are passing legislation to allow self-driving cars, in part hoping to attract Google or Tesla or Uber dollars. But insurance companies are taking a wait-and-see attitude. They’re already planning how they’ll insure self-driving cars (who has the liability?), but they’re in no rush to do so--there are still too many unknowns.

As one insurance executive told me: “Politicians can make self-driving cars legal. The real question will be: can you insure one?”

Or take climate change. One immediate step, given increased extreme weather and sea-level rise, might be to limit construction on low-lying coastal land in hurricane zones.  But government doesn’t want to tell voters, no, you can’t build a house there. Insurance companies, on the other hand, are perfectly willing to say they won’t insure it.

But government doesn’t want to tell voters, no, you can’t build a house there. Insurance companies, on the other hand, are perfectly willing to say they won’t insure it.

And insurers aren’t just saying “no.” One company I work with, for example, has a laboratory that tests building materials in extreme weather conditions. The goal: requiring resilient materials as a prerequisite for insurance coverage.

A very recent example is computer security. Security experts will tell you that most corporate hacking cases are not the result of brilliant hackers. They’re the result of careless security. And bad cybersecurity is starting to impact the market value of companies.

Sounds like another role for insurance. But until recently, cybersecurity insurance was a tricky proposition--insurance companies weren’t sure how to assess the risk. Now, however, insurance companies are beginning to formulate security requirements for companies who seek cyberattack coverage.

In the early 20th century, insurance companies had real impact on increasing factory safety, because they required certain levels of safety before issuing workers’ compensation insurance. A full century later, they may well do the same with cybersafety.

One trend is clear: the “virtualization” of our world has greatly accelerated. Work from home, telemedicine, virtual shopping, distance learning, socializing, exercise: more activities than we might imagine will move to the virtual world during the rest of this decade. This will impact almost all sectors of business and society.

The winners will be those who choose wisely what must stay in the real world and what is best done virtually.

A few more possibilities:

- Instead of fully restaffing, business will invest in artificial intelligence and robotics.

- Businesses will move to either “luxury, full-service” or “everyday low prices,” with diminishing focus on the middle market.

- Businesses will move to either “luxury, full-service” or “everyday low prices,” with diminishing focus on the middle market.

- A new focus on personal wellness, with widespread use of apps and wearable health sensors.

- Hyper-local social networks and community organization will grow in importance. The “sharing economy” may come to mean actual sharing, rather than Uber.

- Consumers will seek a sense of control and sustainability in their personal lives: health, shopping, transportation and more.

- Society will rethink the size, influence and responsibilities of social media and Big Tech.

- The COVID crisis will transition into another crisis: disasters due to extreme weather. Are there tools and practices from COVID that can help with this new threat?

And one hopeful prediction:

- Scientists master rapid vaccination development, governments create smart global health monitoring systems, and COVID becomes the last human pandemic in history.

I spent last summer writing in the farm country of Sicily, a place that usually seems very far from the future. It’s the land where ancient Greek myths lurk in the landscape and the local language, still widely spoken in lieu of Italian, is the oldest in Europe.

The other day I was talking to a young friend, Fabio. Fabio deftly uses all the latest tools of technology to promote his agriturismo business, but keeps them in a clear perspective. “The future,” he told me over a lunch of pasta con limone, “is sometimes the past.”

Fabio offered an example: when he inherited his grandfather’s citrus orchards they had fallen into disuse. Cheaper fruit from Spain and Morocco and Egypt had flooded the European market. But then organic food became popular and Sicily proved to be the gold standard for organic; most farmers there had never used chemicals in the first place. Now Fabio’s lemons are profitable again.

In a similar way I suspect that as artificial intelligence and robotics remove the human element from more and more of what we do, we will find skills from the past become more relevant again. The resurgence of handcrafted goods and food is one example; the art of conversation is another.

When we use new technology to reshape how we work or live, we shouldn’t forget the value of what has come before. As Fabio learned: sometimes the future turns out to need the past.

Recently, an HR director told me that her company is planning a “remedial social skills” course for some of its new employees.

What exactly, I wondered, does that include?

For starters, she said, how to decide when to text, when to send email, when to make a phone call, when to show up in person for a chat.

That makes sense, I said. It’s a kind of business etiquette. After all, someone had to teach the Baby Boomers not to type in ALL CAPS.

But the real focus, she said, would be this: how to start a conversation, and how to know a conversation is over.

I found that disturbing--until I thought about it a bit.

The generation entering the workplace now is the first to grow up with texting and instant messaging as central ways to communicate. Both are ”asynchronous”--you always have time to think about your reply, even if all you text back is “LOL.”.

Face-to-face conversation, on the other hand, is real-time and spontaneous. Some kids, of course, are naturally social. But not all. If you’re an awkward adolescent, a bit unsure about what to say, which communication method would you choose?

This doesn’t mean the problem is with the technology--texting and IMing are here to stay. The problem is that we adults didn’t realize that now there may be another skill we need to start teaching, probably as early as elementary school.

The question of what we should teach will become ever more crucial as artificial intelligence enters the workplace. Skills like empathetic communication (which includes, among other things, conversation) and creative problem solving are two of the unique human abilities that machines won’t easily replace.

But at the same time, kids who grow up with one foot in the virtual world may have less and less opportunity--or need---to practice those skills. Some of the abilities we once took for granted, like conversation, may now need a bit of extra help in the classroom.

Amazon continues to expand its enormous presence in the robotics industry, particularly in terms of warehouse automation. Now both retail and fast food companies are also pushing forward in automating all aspects of their business.

Even so, employers continue to argue that automation will simply create new jobs for humans.

As employers struggle post-COVID to hire workers, it's growing clearer and clearer that the majority who can afford to do so will invest in artificial intelligence and automation. Unlike human employees, technology gets cheaper as it gets better at the job, and as a capital expense it's handy for company finances.

Long-term, robotics and artificial intelligence will fundamentally alter the face of work in ways that our society is very poorly equipped to handle. The "new jobs" will not appear out of thin air--smart management will need to look ahead to how to use existing staff to improve their quality of service.

It's a topic that very few politicians want to address, but which at some point later in this decade will rise to the level of a potential workforce disaster.

For decades now climatologists have agreed that the first symptoms of global warming would be extreme weather events. (Here’s my 1989 Los Angeles Times article on the early researchers in the field.)

And I’ve argued that it will be extreme weather events that catalyze public opinion to demand further climate action from both governments and corporations. As humans, we really can’t perceive “climate”--it’s just too long a time frame. What we do understand is weather.

And I’ve argued that it will be extreme weather events that catalyze public opinion to demand further climate action from both governments and corporations. As humans, we really can’t perceive “climate”--it’s just too long a time frame. What we do understand is weather.

We’ve always named the traditional forms of extreme weather: cyclones and hurricanes. But in 2015 the UK started also naming severe storms (Angus, in 2016, disrupted transportation throughout the country). And severe storm names are growing more popular in the US (Jonas, the same year, set numerous East Coast records).

This summer, Europe is in the midst of a record-setting heatwave, and it’s been named as well: Lucifer. In the act of naming extreme weather events, we take them more seriously, and perhaps we will ultimately demand that our governments do the same.

I worked last week with a major credit card company, and one topic was whether cash will disappear. Will there come a day when all transactions are electronic, perhaps using your smart phone--or even, say, just your fingerprint--and cash will be kept only in museums?

Some countries are almost there--in Sweden, for example, half the banks keep no cash on hand. Many restaurants and coffee houses no longer accept cash and churches, flea markets and even panhandlers take mobile phone payments.

Some countries are almost there--in Sweden, for example, half the banks keep no cash on hand. Many restaurants and coffee houses no longer accept cash and churches, flea markets and even panhandlers take mobile phone payments.

For merchants, going cashless lessens the threat of robbery and eliminates daily treks to the bank. This summer in the United States, Visa International announced it will give $10,000 grants to selected restaurant and food vendors who agree to stop accepting cash. (Merchants, of course, also pay a fee for every electronic transaction, significantly more in the US than in Europe.)

So is this the end of cash? As the saying goes, it’s complicated.

Electronic payments may be more convenient, but cash is still anonymous. As a result cash fuels criminal ventures as well as tax evasion. Large bills, in particular: $50,000 in $100s is a convenient stack only about 4 inches high. The EU will stop printing €500 notes, a criminal favorite, in 2018 and there are calls to eliminate the $100 bill in the US. And cash also powers the underground economy for tax evasion.

Governments, in short, might be just as happy to get rid of cash entirely. But many law-abiding citizens consider the privacy of cash a valuable option--even though they may not actually take advantage of it very often. It’s comforting to know that it’s there, and they’re likely to complain loudly if it’s threatened. When India removed some large bills from circulation in late 2016, the result was a months-long national crisis that nearly brought down the government.

My guess is that governments won’t go to the trouble of eliminating cash. What they will do is make cash increasingly less attractive to use. In southern Italy, where I spend part of the year, the “black” economy is huge--work is done off the books and paid for with cash. But the Italian government has gradually made it harder to withdraw or deposit even moderate amounts of cash at the bank without paperwork and questions. (The U.S. has similar bank regulations but for much larger amounts. For now.)

On the other end of the scale, next year Italy will also stop minting 1 and 2 cent coins. Merchants will still be allowed to price merchandise at, say, €1.99--but you’ll only get that price if you pay electronically. For cash, the price will be rounded up to €2. The result is another subtle nudge toward cashless transactions.

On the other end of the scale, next year Italy will also stop minting 1 and 2 cent coins. Merchants will still be allowed to price merchandise at, say, €1.99--but you’ll only get that price if you pay electronically. For cash, the price will be rounded up to €2. The result is another subtle nudge toward cashless transactions.

Cash is likely to be with us much longer than many futurists predict. The real question may be: who will bother to use it?