Blog

What enormous year-end event could possibly cause media ranging from CNN, the BBC, Newsweek, and NPR to The Globe and Mail and Mental Floss to call the Practical Futurist for an interview?

Try the 1989 movie “Back to the Future 2”--which happens to be set in 2015 and is thus full of predictions for our upcoming year.

The reporters were particularly interested in what the film got wrong, which includes both Doc’s flying car and Marty McFly’s hoverboard. Of course futurists have been getting the flying car wrong since at least 1957, when Popular Mechanics featured a flying car on the cover. They cautioned in the article, however, that we wouldn’t actually have them until 1967.

The reporters were particularly interested in what the film got wrong, which includes both Doc’s flying car and Marty McFly’s hoverboard. Of course futurists have been getting the flying car wrong since at least 1957, when Popular Mechanics featured a flying car on the cover. They cautioned in the article, however, that we wouldn’t actually have them until 1967.

And the hoverboard? Entrepreneurs have lately come up with a version, but it functions magnetically and thus only floats above metal surfaces. Marty’s hoverboard, on the other hand, floats over anything and the only way I can imagine it might work is anti-gravity. Alas, in 2015, it’s unlikely we’ll even have a complete theory of gravity.

On the other hand, BTTF2 got some things right: Marty uses a thumbprint to pay for a taxi ride (shades of the iPhone 6); TV screens are flat and wall-sized; video telephone calls are increasingly common.

Of course, BTTF2 wasn’t meant to be a futurist manifesto but rather an entertaining movie. And it certainly succeeded at being memorable, considering the number of journalists who are writing about it 26 years later. (We’ll see how many articles appear at the end of 2018 about “Bladerunner”, which was set in 2019.)

But it’s also a good reminder of the difference between futurism and science fiction. New technologies can run into all sorts of financial, governmental and social problems that the fiction writer can happily ignore. For example: even if you could build a reasonably-priced flying car, you’d need new infrastructure for landing, a whole new range of driver skills and the approval of government agencies from the Department of Transportation to the FAA.

But it’s also a good reminder of the difference between futurism and science fiction. New technologies can run into all sorts of financial, governmental and social problems that the fiction writer can happily ignore. For example: even if you could build a reasonably-priced flying car, you’d need new infrastructure for landing, a whole new range of driver skills and the approval of government agencies from the Department of Transportation to the FAA.

And thus a good futurist needs to understand not just technology, but the worlds of business, government, and human nature.

Human nature was one thing that BTTF2 got right. My favorite prediction was that objects from the 70s and 80s would become sought-after antiques in 2015. Sure enough, a couple of weeks ago, an Apple I from the mid-’70s sold at auction for $360,000. Don’t ditch that 1984 Mac quite yet!

I was speaking in Iowa City earlier this week and was reminded again of how vital many Midwestern cities have become. At the same time, a new research group, City Observatory,  released a report about where young college graduates are moving. As we already know, they like to move to cities. But, as an excellent New York Times summary points out, what’s interesting is that cities like Nashville, Austin, Portland, Buffalo, Pittsburgh and St. Louis have had the highest percentage increase of young graduates since 2000, all significantly higher than New York City.

released a report about where young college graduates are moving. As we already know, they like to move to cities. But, as an excellent New York Times summary points out, what’s interesting is that cities like Nashville, Austin, Portland, Buffalo, Pittsburgh and St. Louis have had the highest percentage increase of young graduates since 2000, all significantly higher than New York City.

I’ve long thought that this is a trend that will continue. As work becomes more virtualized, and cities like New York and Los Angeles become increasingly expensive, it simply makes sense that both employers and employees will look to cities that offer more affordable lifestyles. That’s going to be especially true when the bulk of the Millennial generation begins to think about having kids.

The Internet has not only made it more possible to work at a distance, but it also enhances the smaller city lifestyle. You don’t have to drive fifty miles to see a foreign film--they’re available, streaming. The Internet takes care of just about any exotic shopping needs. There’s the Metropolitan Opera in live HD in your local theater. And given the speed at which trends now spread across the country, the latest artisanal kale shop will probably show up in your neighborhood only a few months after it debuts in Brooklyn.

Yet real estate developers in the major cities continue to build new apartments at a record pace. In New York City alone, developers like to say there are another million people on the way. But I’m not so sure. People like cities, and I don’t expect any reversal of our species‘ five-thousand-year march into urbanization. But when you add in the new factor of virtual work and life, I don’t think bigger (and more crowded and more expensive) will continue to be better.

Yet real estate developers in the major cities continue to build new apartments at a record pace. In New York City alone, developers like to say there are another million people on the way. But I’m not so sure. People like cities, and I don’t expect any reversal of our species‘ five-thousand-year march into urbanization. But when you add in the new factor of virtual work and life, I don’t think bigger (and more crowded and more expensive) will continue to be better.

Yesterday the Sony Computer Science Laboratories --Sony’s elite corporate think-tank--gave its first symposium in New York City, at the Museum of Modern Art. As is appropriate for an independent think tank, some of the ideas were visionary to the point of dream-like, such as 3D-printable  gardens. Others were of the ilk that make perfect sense but will be tough to implement in the real world, such as a microgrid power system that used DC rather than AC power plus wind and solar power to create energy-independent neighborhoods. Probably not practical for the developed world, but at the right price, ground-breaking in developing countries where large percentages of the population don’t have electricity to start with.

gardens. Others were of the ilk that make perfect sense but will be tough to implement in the real world, such as a microgrid power system that used DC rather than AC power plus wind and solar power to create energy-independent neighborhoods. Probably not practical for the developed world, but at the right price, ground-breaking in developing countries where large percentages of the population don’t have electricity to start with.

But the most remarkable demonstration for me was very close to Sony’s own home turf: an artificial intelligence system that is able to listen to a musical performer and extract their “style”, rather than recording the actual notes. The system can then create new pieces of music in the style of the performer, or accompany a real musician in the style of a particular accompanist. Researcher Francois Patchet showed examples of a John Coltrane song done in the style of Wagner, a Brazilian ballad performed in the style of the a cappella group Take 6, and an original composition in the style of jazz legend Bill Evans. A good piece in The Atlantic took a more in-depth look at this last month.

Interesting detail: while the software will take bits and pieces of a composer’s work, it is constrained from copying so much as to constitute plagiarism. It’s a fine line, of course, that hip-hop artists have struggled with in the process of sampling over the years. But Patchet took the intellectual property question an additional step. Recorded music, he pointed out, thanks to everything from illegal downloading to low-cost streaming services, is getting to be pretty low-value these days. “The real new asset of value,” said Patchet, “is style.”

additional step. Recorded music, he pointed out, thanks to everything from illegal downloading to low-cost streaming services, is getting to be pretty low-value these days. “The real new asset of value,” said Patchet, “is style.”

I have a feeling that’s a concept that the lawyers over at Sony Music are thinking about right now. Sony co-owns the largest music library in the world, including, oh, the Beatles and Michael Jackson. If a computer is smart enough to listen to the entire Michael Jackson oeuvre, and then write “new” Michael Jackson songs, just where do those royalties go?

I saw a great presentation last week at a wearable computing conference, by the wearables group at Motorola--a team that’s really focused on building Google Glass-like equipment for industry, rather than consumers.

Google Glass, Fashion Version

Google Glass, Fashion Version

It was interesting that even at this small industry event, no one in the audience quite agreed on what to call these embryonic devices. Of the two most popular phrases--”head-mounted displays” or “smart glasses”--I think I’ll take the latter. Although now it looks Google is making progress in making “glass” legally it’s own. (Hopefully if Apple introduces a version they can call them i-glasses.)

It made me realize that adoption of smart glasses will probably be a throwback to the patterns of the last century, when commercial applications came first and then the technology migrated to consumers. (Of course, that pattern has been turned on its head this century--employees tend to have better computers and phones in their homes than they do at work.)

It’s pretty clear that the first compelling applications of smart glasses will initially be in areas like public safety (firefighters, for example), equipment maintenance workers, maybe warehouses and logistics--areas where people need detailed and up-to-date information, while keeping their hands free. Because it's such advanced technology, the first really usable smart glasses are going to be expensive, as well.

Not Google Glass

Not Google Glass

It’s probably going to be a bit like the adoption curve of tablet computers. Twenty years ago, Fujitsu was already making a good business out of tablet computers for specialized purposes like healthcare, inventory and sales.

Then in 2001 Microsoft tried to introduce the Tablet PC more broadly, and it was pretty much only early adopters who bought it. I was one of them. Frankly, it was a bit of pain--you had to use a special pen, for starters--but it certainly got lots of attention from curious passengers on airplanes. All in all, not unlike today’s Google Glass.

Finally, in 2010, touch screens plus better interfaces came along and the tablet was launched--twenty years after Fujitsu started selling them.

I suspect it will be the same with smart glasses--although they will be mainstream far more quickly than the tablet did, thanks to Moore’s Law and our increasingly rapid acceptance of new technology.

Most of my speaking is for private organizations. But if you happen to be in New York on July 29, I’ll be speaking at the Adorama store at 42 W. 18th Street, not far from Union Square, at 4 PM and 6 PM.

Not 2020, actually

Not 2020, actually

Adorama, of course, is the 35-year-old camera store that has grown to be one of the leading online consumer technology retailers in the US. My topic is Tomorrow’s Technology--gazing out at my favorite year, 2020--so I’ll be looking at wearables, smart objects, cloud-based intelligence and more.

I confess that I get a lot of my best anecdotes from the audience, so there will be plenty of time for Q&A and discussion. I’m looking forward to hearing technology consumers talk about their thoughts on the future.

Tickets are free; Adorama suggests registration here. Hope to see you there!

The phrase "generation gap" first appeared in the Sixties, when the unprecedented social upheaval of that decade truly created a cultural chasm not just between generations, but even within families. These days "generation gap" sounds a bit old-fashioned, but I'd say that for the first time in forty years, the condition it describes is back.

Not, this time, in families--indeed, the children of the Baby Boomers are emotionally closer to their parents than any generation in history. (Also physically closer, when they move back home after college.)

Not, this time, in families--indeed, the children of the Baby Boomers are emotionally closer to their parents than any generation in history. (Also physically closer, when they move back home after college.)

Now the gap is in the workplace. No matter what kind of audience I speak to--from educators to lawyers to venture capitalists--and no matter what the topic is, during the Q&A session there's always some form of the question "What's up with these kids, anyway?"

The questions--well, more accurately, complaints--range from lack of social skills to attention span to reading ability to work ethic to that perennial favorite, "entitlement".

All of that makes for some lively discussion, but at the end I have to say: these are, in fact, your future employees and customers. And one way or another, you're going to have to learn to live with them.

That's why I'm looking forward to speaking at a conference this July at Colorado State University in Ft. Collins called "Why Hire Gen Y?". The agenda begins with the assumption that Gen Y--the Millennials--are not only an inevitable part of the workforce, but that they also will bring new strengths.

"What's up with those kids?" is a serious question that deserves a thoughtful response. And that's something that should particularly be appreciated by anyone who stood on the opposite side of the generation gap forty years ago.

During the last year I’ve watched the conversation among economists and labor experts go from the traditional “Automation always destroy jobs but then it creates more jobs” to “Uh, maybe it’s different this time.”

It is different this time. Between robots, sophisticated artificial intelligence, and flexible global outsourcing, we’re going to eliminate a lot of jobs and it’s no longer clear where the new jobs--at least well-paying ones--will come from. A detailed Oxford University analysis last year said that nearly half of current jobs can be automated.

Coincidentally, over the last few months I’ve been working with a Minneapolis-based group called Nexstar, that helps home service providers--electricians, plumbers, heating and air conditioning contractors--manage their businesses. Their members are financially successful local companies, often with multiple locations.

One problem they share, however, is this: where is the next generation of their employees coming from?

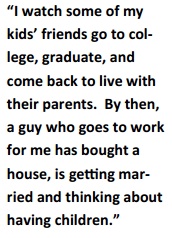

Being a plumber or electrician is not a sexy job for kids growing up in a world of high tech billionaires. Yet these are jobs that can support a solid middle-class lifestyle. As one electrical contractor told me: “I watch some of my kids’ friends go to college, graduate, and come back to live with their parents. By then, a guy who goes to work for me has bought a house, is getting married and thinking about having children.”

My advice to these companies was that they need to tell a new story about jobs in the trades--not just to potential employees, but to teachers, school board officials and parents. The story has three parts:

--These are jobs that can’t be outsourced or automated. No matter how much Internet bandwidth you have, you’ll never be able to hire someone in Bangalore to change your kitchen faucets. And high on the list of jobs that can’t be done by robots involve physical dexterity in small spaces and flexible problem solving.

--These are jobs that, increasingly, use high technology like smart smart sensors and automated systems to control both electricity and plumbing. Home contractors are right at the interface between the physical world and the “Internet of things.”

--Finally, these are jobs that will help save the planet. We’re on our way to 9 billion humans by the middle of the century, many with middle-class lifestyles that will increasingly tax both our energy and water resources. By the Twenties, energy and water conservation will become major concerns--and an increasing part of electrical and plumbing and HVAC work.

In the United States educational system high schools measure their success by how many graduates go on to higher education. Yet many of those students fail to complete their degrees. And even if they do, four years of college may not give students much more than a lot of debt and a job at Starbucks. Maybe it’s time for policy-makers to broaden the definition of “a good job” beyond the confines of the office cubicle.

Regular readers know that my favorite form of communication is public speaking, and I'm occasionally asked where people might be able to see me. Alas, almost all of my engagements are private, so I usually don't have a good answer. But this spring and summer I have a few public speeches, and I'll mention the first of them today.

BlueWater Technologies is a Michigan-based company that specializes in high-end audio and video technology for installations and meetings. They're also known for an annual full-day event in Detroit called TechExpo that showcases the latest in AV tech and related gadgetry along with educational sessions (and meals, and entertainment). This year's TechExpo is May 21st at The Fillmore - Detroit. And they're currently offering tickets at half-price, so that makes it an even better deal.

BlueWater Technologies is a Michigan-based company that specializes in high-end audio and video technology for installations and meetings. They're also known for an annual full-day event in Detroit called TechExpo that showcases the latest in AV tech and related gadgetry along with educational sessions (and meals, and entertainment). This year's TechExpo is May 21st at The Fillmore - Detroit. And they're currently offering tickets at half-price, so that makes it an even better deal.

Recently, between speeches, I’ve been restoring an old stone farmhouse in Sicily. In many ways Sicily is a step back in time (a great tonic for a futurist); it’s also often a reminder of how life works in a culture where the virtual world is still just gaining a foothold.

One morning in Sicily I needed to order a bathtub. I was buying from the same store where I’d initially seen the tub, they had sold me lots of other plumbing fixtures and already had all my financial information on file. All I wanted to do was place the order.

In New York City we would have done this by email. In Sicily, however, there was another visit, coffee, nice conversation, the careful writing of the invoice by hand, a bit more conversation, then “Ciao”. (Later I would receive, by email, an electronic version of the order; it had been entered into the computer after I left.)

On the same trip I asked the kitchen designer if he could email me PDFs of the final shop drawings. Instead he set up an appointment. A coffee, nice conversation, a careful and leisurely review of the shop drawings, some additional conversation, and only then—a copy of the shop drawings.

Efficient? Certainly not. But once I let go of my American timeframe, it was pleasant and enriching. Somehow it reminded me of a morning, years ago, in Senegal, when I watched a street merchant selling kola nuts, the caffeine-rich berries that are West Africa’s morning cup of coffee. Each customer would stand, perusing the tray of nuts, a conversation would begin and after a few minutes, the deal would be done. Finally I went up and bought my own kola nut. It cost something like one-sixth of a cent—an amount that to my American mind seemed radically out of scale with the amount of time each customer took to purchase.

Of course, in both Sicily and Senegal, the point wasn’t simply the transaction, but the social event as well.

For years I’ve told retailers that their virtual stores must duplicate the social environment of their physical stores; when I go into a virtual store I need to be able to look around and see if any of my friends are shopping there also.

That’s the element that “social shopping” startups are restoring to the world of e-commerce. Sites ranging from Polyvore to Pinterest let friends and family make suggestions and comment on your shopping, mimicking the social event of a group visit to the mall. And they’re driving a lot of purchases.

But what Sicily reminded me was that there is another social element retailers need to integrate: the relationship between the seller and the customer. Sure, sometimes you’d rather just make the order and get out. But other times, a salesperson who really knows their product is a great pleasure. Beyond simple information, there is also a very old and traditional social exchange that can enrich both customer and salesperson.

Some might suggest that Americans no longer value that kind of exchange, but I suspect they’re wrong. It’s something we need to duplicate in the virtual world, in some way that’s more tangible and social than pop-up instant messaging boxes. And perhaps more importantly, that salesperson-customer relationship, properly managed, will continue to be a strong advantage for the brick-and-mortar world.

Lately I’ve had a number of requests for my speech “How to Use the Downturn to Rethink and Thrive”, which demonstrates a couple of things. First: the economy still isn’t out of the woods (no surprise). And second: more and more organizations realize that the past five years have seen fundamental shifts in business and society that will hinder their recovery even when better times return.

In short: The rising tide, when it comes, may not lift all boats—unless you’ve been upgrading your boat in the meantime.

Thus there’s a new openness among executives to learning about future tools and techniques. But then there’s usually also a question: how do we sell these new ways of working to our managers and staff? Just this month I’ve heard versions of that question from school administrators in the Midwest, convenience store operators in Atlanta and a major insurance brokerage in California.

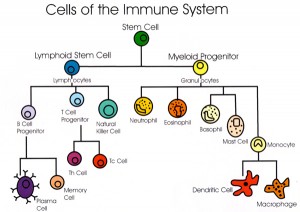

My answer? Consider our bodies’ immune system. It’s a wonder of nature: a team of various agents, from macrophage to T-cells, highly evolved to attack bacteria, viruses, allergens, anything that looks like a foreign invader.

And just like the body, organizations have also developed immune systems--but these systems attack outside ideas. Long ago, that was probably generally a good thing. Business moved slowly, the world didn’t change much, and most new ideas were probably just going to waste time and money.

But now. too often, the corporate immune system attacks good ideas. Like the body’s immune system, there can be multiple agents in the corporate immune system. Sometimes it might be the lawyers. Corporate lawyers don’t usually get fired for saying “no.” In fact I once worked with one for whom I prefaced every idea with the plea “Please don’t say no until I finish talking.”

But now. too often, the corporate immune system attacks good ideas. Like the body’s immune system, there can be multiple agents in the corporate immune system. Sometimes it might be the lawyers. Corporate lawyers don’t usually get fired for saying “no.” In fact I once worked with one for whom I prefaced every idea with the plea “Please don’t say no until I finish talking.”

Or, more surprisingly, it can be the sales staff. Salespeople like to know their product, so they appreciate New and Improved! But they don’t necessarily like Altogether New. (Years ago the newspaper business learned that when they trained their print sales people to also sell online ads. But the print people were never fully comfortable with the online lingo--and thus online ads never seemed to come up in the sales calls.)

In fact, immune agents can be any job-title in your business, up to and including the board of directors. As a result, when you encounter resistance to new ideas, you first need to identify which part of the corporate immune system has switched on. Next—and here’s the hard part for true innovators--you need to make your new idea look as much as possible like something that’s already being done. And then, with some gentle urging, you can get that new idea past the corporate immune system and into practice.